- Summary

- Symptoms

- Read More

Summary

Charcot joints occur when the ability to sense deep pain is diminished or lost. As a result of the inability to sense pain, small fractures begin to develop in bone subject to mechanical stress. The normal response to a fracture is swelling and increased blood flow to the broken bone. The increase in blood flow tends to "wash away" calcium from the fracture site, resulting in weakening of the bone and further fractures. In a healthy individual, pain would limit load bearing to the bone. If that loss of protective sensation (LOPS) is absent, a cycle of increasing fracture activity begins with progressive collapse of the supporting bone.

pain, small fractures begin to develop in bone subject to mechanical stress. The normal response to a fracture is swelling and increased blood flow to the broken bone. The increase in blood flow tends to "wash away" calcium from the fracture site, resulting in weakening of the bone and further fractures. In a healthy individual, pain would limit load bearing to the bone. If that loss of protective sensation (LOPS) is absent, a cycle of increasing fracture activity begins with progressive collapse of the supporting bone.

Symptoms

- Swelling, warmth, and redness in the mid-foot, rearfoot or ankle

- Inability to fit the foot into a shoe

- Collapse of the arch of the foot

The symptoms of Charcot joints vary based upon the location and severity of the condition and LOPS. The initial symptom of a Charcot joint is localized edema (swelling) of the joint or joints. The edematous area may exhibit increased temperature. Often, the first noticeable symptom that a patient with advanced peripheral neuropathy will notice is the fact that their shoes have become tighter or they have difficulty fitting into a pair of shoes that have fit well for some time. The most common area of the foot to be affected by a Charcot joint is the mid-arch. Charcot joints can also develop at the rearfoot and ankle, but development at these locations is much less common.

The challenge in diagnosing this condition is the lack of overt symptoms. Peripheral neuropathy often masks the onset of initial Charcot symptoms. As a result, the physician needs to rely more on clinical symptoms and less on the history and physical exam. Charcot joints are one more reason why diabetes counseling and education are so very important.

Description

The description of Charcot joints dates back to 1703 when neuropathic osteoarthropathy was first described by W. Musgrave. Jean Marie Charcot is credited for his work in 1868 for describing gait anomalies of patients who had lost sensation of the lower extremity due to syphilis (tabes dorsalis.) Jordan, in 1936, was the first to describe a relationship of diabetes to neuropathic arthropathy. Today, the vast majority of cases of Charcot joints are due to the loss of sensation (peripheral neuropathy) in the feet due to diabetes.

The rate of progression of a Charcot joint depends upon several variables. Any ability to perceive pain may lead to a more prompt diagnosis due to a patient's concern regarding their abilities to complete an average day. Complete loss of protective sensation (LOPS) may delay early diagnosis. Charcot joints are easily confused with osteoarthritis, which is treated much less aggressively than a Charcot joint.

In 1966 Eichenholz proposed a classification of Charcot joints which is broken down into three distinct stages. Stage one, or the development stage, shows debris surrounding the joints on x-ray. Stage one can develop over a period of days to weeks and is merely radiographic change that occurs in response to unperceived trauma. Stage two is the coalescence stage. In stage two, the bone begins to heal with absorption of debris and healing of large fracture fragments. Stage three, often called the reconstruction or reconstitution stage, notes a reduction in bone turn over and reformation of stable bone structure. Stage 0 was added in 1999 by Sella and Barrette to include patients who exhibit clinical symptoms of Charcot arthropathy but have yet to show radiographic changes.

reformation of stable bone structure. Stage 0 was added in 1999 by Sella and Barrette to include patients who exhibit clinical symptoms of Charcot arthropathy but have yet to show radiographic changes.

The classification proposed by Brodsky in 1992 includes the location of the Charcot joint and is commonly used in clinical practice today. Brodsky's classification is as follows:

Type 1 - Lisfrank's joint - 27-60% of all Charcot joint deformities of the feet

Type 2 - Chopart's joints and subtalar joints - 30-35%

Type 3A - Ankle joint - 9% of all Charcot deformities

Type 3B - The posterior calcaneus

Type 4 - Multiple regions of the foot and/or ankle

Type 5 - The forefoot

Charcot joints are often not diagnosed until they create another problem that affects a patient's normal activities. These may be as simple as an inability to fit into shoes or as severe as an infected ulceration of the foot. By this stage, the Charcot deformity has in all likelihood progressed to a point where there is significant displacement of the bones and joints along with multiple displaced fractures.

Charcot joints are often not diagnosed until they create another problem that affects a patient's normal activities. These may be as simple as an inability to fit into shoes or as severe as an infected ulceration of the foot. By this stage, the Charcot deformity has in all likelihood progressed to a point where there is significant displacement of the bones and joints along with multiple displaced fractures.

The most common long-term complicating factor of a Type 1 Charcot joint is a rocker bottom foot. A rocker bottom foot is a prominence on the bottom of the foot that results from the collapse of the arch. In an advanced rocker bottom foot, the inability to sense pain becomes a complicating factor for the skin. As the bone places more pressure on the skin, the skin begins to ulcerate and becomes infected. Bone infection and loss of limb is common with rocker bottom feet.

Causes and contributing factors

Any condition that contributes to the onset of peripheral neuropathy may be considered a contributing factor to a Charcot joint. These conditions include:

Amyloid

Degenerative change of the spinal cord or peripheral nerve

Diabetes mellitus

Familial-hereditary neuropathies including Charcot-Marie Toothe Disease, Hereditary sensory neuropathy and Dejerine-Sottas Disease

Hansen's Disease (Leprosy)

Pernicious Anemia

Spinal cord injury

Tabes dorsalis (neuropathy caused by syphilis

Transverse myelitis

Tumors of the spinal cord

Medications that may be a contributing cause of Charcot joints include:

Indomethacin

Injectable and systemic use of steroids

Phenylbutazone

Vincristine

Other factors that may contribute to causing neuropathy and, subsequently, Charcot joints include:

Alcoholic neuropathy

Congenital insensitivity to pain

Pott's Disease (tuberculosis of the spine)

Differential Diagnosis

Bone tumor

Cellulitis

Diabetic osteolysis

Fracture

Gout

Idiopathic edema

Lymphedema

Osteoarthritis

Pseudogout

Rheumatoid arthritis

Septic arthritis

Soft tissue tumor

Treatment

The hallmark of treatment of Charcot joints is early diagnosis and prevention. The symptoms and findings of Charcot joints vary, so each case requires careful evaluation. Treatment of Charcot joints of the feet may include rest, casting, and non-weight bearing to allow adequate time for fracture healing. Total contact casting, a TOAD brace or the use of a Charcot Restraint Orthotic Walker (CROW) are popular in stages one and two. The goal is to limit weight bearing to enable progression to stage three. This progression can take from several weeks up to 6 months. Electrical stimulation, or bone stimulation, is a popular adjunct to non-weight bearing or casting.

requires careful evaluation. Treatment of Charcot joints of the feet may include rest, casting, and non-weight bearing to allow adequate time for fracture healing. Total contact casting, a TOAD brace or the use of a Charcot Restraint Orthotic Walker (CROW) are popular in stages one and two. The goal is to limit weight bearing to enable progression to stage three. This progression can take from several weeks up to 6 months. Electrical stimulation, or bone stimulation, is a popular adjunct to non-weight bearing or casting.

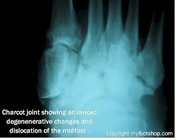

X-rays are the single most useful tool in diagnosing Charcot joints. MRI and bone scans are helpful in the early phases of Charcot joints (Eichenholz stage 0) and are sensitive indicators of hyperemia (increased blood flow to the area of the fracture) and bone edema. Surface skin temperature is the most reliable indicator of the activity of the fractures. Most doctors do not keep the necessary equipment to measure skin temperature but merely measure with direct touch to sense the presence or lack of warmth.

Surgical procedures for Charcot joints are often challenging, not only due to the complexity of this condition but also due to the fact that these patients are usually poor surgical candidates due to other health problems (co-morbidity.) Surgical procedure may include reconstruction of the arch and/or joint fusion. Often, surgical procedures are used to return the foot to a shape that can be accommodated by normal footwear. Stage three Charcot deformities often result in lumps, bumps, and unusually shaped feet due to bone changes. Reshaping the foot may be used to eliminate a bony prominence on the top or bottom of the foot.

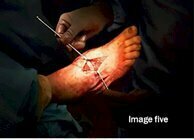

The following pictures show the steps of a surgical correction of a Charcot joint using a reverse Cole procedure and Achilles tendon lengthening. Image one shows the foot prior to surgery with a rocker bottom deformity. Images two and three show dissection of the midfoot and the surgical cut through the midfoot. The cut is made in a wedge shape with the apex dorsal and point plantar. Images four and five show placement of the autogenous bone graft fashioned from a cadaver femoral head. Finally, image six shows restoration of the arch and initiation of fixation of the graft.

When to contact your doctor

All suspected Charcot joints should be evaluated by your podiatrist or orthopedist.

References

References for this article are pending.

Author(s) and date

This article was written by Myfootshop.com medical advisor Jeffrey A. Oster, DPM.

This article was written by Myfootshop.com medical advisor Jeffrey A. Oster, DPM.

Competing Interests - None

Cite this article as: Oster, Jeffrey. Charcot Joint. https://www.myfootshop.com/article/charcot-joint

Most recent article update: November 21, 2020.

Charcot Joint by Myfootshop.com is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Charcot Joint by Myfootshop.com is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.